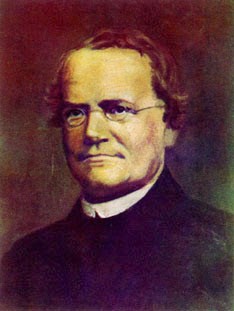

Gregor Mendel: Christ Follower, Scientist, and Father of Genetics

Gregor Mendel: Christ Follower, Scientist, and Father of Genetics

Gregor Johann Mendel was born on 20 July 1822 to a devout Christian family in Heinzendorf, Moravia, in what was then Silesia, Austria, and now the Czech Republic. His father, a Napoleonic War veteran, and his mother taught their children to love God and, although poor, instilled a passion for learning in their three children, Gregor and his two sisters. All of them worked hard on their multi-generational family farm, studying between chores and harvests, and struggling to pay for school. Gregor especially loved natural science and mathematics, two areas in which he excelled.

At eighteen years old, Gregor entered the University of Olomuoc, a Jesuit school located in the capital of Moravia. There he studied philosophy, physics, and mathematics, and upon graduation three years later, he joined the Augustinian Order and became a monk. In the next few years, at the Augustinian Monastery of St. Thomas in Brno (then Brünn), the young scholar-theologian was ordained to the priesthood. He continued his scientific studies, sometimes traveling to the University of Vienna to learn under the instruction of the famous experimental physicist Christian Doppler, who discovered the Doppler Effect. He also took advantage of the monastery's five-acre botanical garden and vast library to conduct his experiments on plant breeding and hybridization. He learned Latin, Greek, Chaldean, Syrian, and Arabic, which helped him in his research.

For the next twenty years, Gregor also taught science in a secondary school. Mendel did not set out to conduct the first well-controlled and brilliantly-designed experiments in genetics. His goal was to create hybrid pea plants, observe, and record the outcomes. His observations led to more experiments, which led to unusually brilliant and insightful conclusions. By simply counting peas, analyzing them under his microscope, and keeping meticulous notes, Mendel established the principles of inheritance, coined the terms dominant and recessive, and was the first to use statistical methods to analyze and predict hereditary information. For eight years, Mendel cultivated more than 28,000 Knight garden pea plants, using a paintbrush painstakingly to transfer pollen from one plant to another to make his crosses (all the while still attending to his duties as a monk and a teacher).

On February 8, 1865, Mendel presented his work to the Brünn Society for Natural Science. His paper, "Experiments on Plant Hybridization," was published the next year and included his three generalizations, all of which later became famous as Mendel's Laws of Inheritance. While his work was appreciated for its thoroughness, no one seemed to grasp its importance at the time. The work was simply too far-sighted, too contrary to popular beliefs about heredity. "My time will come," Mendel once wrote to a friend, but it was more than thirty years before his work was understood. What he actually did was to discover and articulate the core foundations of genetics - identified the basic paired elementary units of heredity (now called genes) and stated the statistical laws governing them. Subsequent scientists, early in the twentieth century, rediscovered both Mendel and his work, replicated his experiments, and refined his conclusions to launch the scientific study of genetics.

In the years following the publication of his work, Mendel continued his interest in science. He attempted cross-breeding experiments with the plant, Hawkweed, and installed fifty beehives at the monastery, a hobby he had learned at his boyhood family farm. He became a meticulous record keeper of meteorological and astronomical data because he wanted to improve weather forecasts for farmers to make their jobs easier. Nine of thirteen of Mendel’s published studies deal with meteorology. He was also elected abbot of his monastery in 1868, and led in protesting the government's crippling taxation of his parish. Gregor Mendel died in 1884 of kidney failure at the age of sixty-one.

Like many great artists, the work of Gregor Mendel was not valued until after his death. He who is now called the "Father of Genetics" was remembered in life as a kind, quiet, shy, and gentle man, who loved flowers and the weather and stars. Everybody loved him. The scientific contributions of Mendel, however, cannot be overstated. His findings have been applied in plant and animal breeding, as well as in medicine and other fields. Modern genetics is the basis of current experiments in cell reproduction and cloning, and is a truly prestigious and celebrated science.

Most of all, Mendel maintained throughout his life a strong belief and hope in God, to whom he had pledged his life. His scientific work, particularly his experiments with pea plants, was not seen as contradictory to his religious beliefs, but as a means to helping others to understand God's creation. His commitment to his faith was evident in his sermons and other writings, which show his passion about sharing his beliefs about God with others on any given occasion. This month, we celebrate Christians who are scientists - those who study the brilliance of God's Creation, for they hold in their hearts two great commitments: one to Christ, and the other to a stewardship of the world God has made.

-Karen O'Dell Bullock

At eighteen years old, Gregor entered the University of Olomuoc, a Jesuit school located in the capital of Moravia. There he studied philosophy, physics, and mathematics, and upon graduation three years later, he joined the Augustinian Order and became a monk. In the next few years, at the Augustinian Monastery of St. Thomas in Brno (then Brünn), the young scholar-theologian was ordained to the priesthood. He continued his scientific studies, sometimes traveling to the University of Vienna to learn under the instruction of the famous experimental physicist Christian Doppler, who discovered the Doppler Effect. He also took advantage of the monastery's five-acre botanical garden and vast library to conduct his experiments on plant breeding and hybridization. He learned Latin, Greek, Chaldean, Syrian, and Arabic, which helped him in his research.

For the next twenty years, Gregor also taught science in a secondary school. Mendel did not set out to conduct the first well-controlled and brilliantly-designed experiments in genetics. His goal was to create hybrid pea plants, observe, and record the outcomes. His observations led to more experiments, which led to unusually brilliant and insightful conclusions. By simply counting peas, analyzing them under his microscope, and keeping meticulous notes, Mendel established the principles of inheritance, coined the terms dominant and recessive, and was the first to use statistical methods to analyze and predict hereditary information. For eight years, Mendel cultivated more than 28,000 Knight garden pea plants, using a paintbrush painstakingly to transfer pollen from one plant to another to make his crosses (all the while still attending to his duties as a monk and a teacher).

On February 8, 1865, Mendel presented his work to the Brünn Society for Natural Science. His paper, "Experiments on Plant Hybridization," was published the next year and included his three generalizations, all of which later became famous as Mendel's Laws of Inheritance. While his work was appreciated for its thoroughness, no one seemed to grasp its importance at the time. The work was simply too far-sighted, too contrary to popular beliefs about heredity. "My time will come," Mendel once wrote to a friend, but it was more than thirty years before his work was understood. What he actually did was to discover and articulate the core foundations of genetics - identified the basic paired elementary units of heredity (now called genes) and stated the statistical laws governing them. Subsequent scientists, early in the twentieth century, rediscovered both Mendel and his work, replicated his experiments, and refined his conclusions to launch the scientific study of genetics.

In the years following the publication of his work, Mendel continued his interest in science. He attempted cross-breeding experiments with the plant, Hawkweed, and installed fifty beehives at the monastery, a hobby he had learned at his boyhood family farm. He became a meticulous record keeper of meteorological and astronomical data because he wanted to improve weather forecasts for farmers to make their jobs easier. Nine of thirteen of Mendel’s published studies deal with meteorology. He was also elected abbot of his monastery in 1868, and led in protesting the government's crippling taxation of his parish. Gregor Mendel died in 1884 of kidney failure at the age of sixty-one.

Like many great artists, the work of Gregor Mendel was not valued until after his death. He who is now called the "Father of Genetics" was remembered in life as a kind, quiet, shy, and gentle man, who loved flowers and the weather and stars. Everybody loved him. The scientific contributions of Mendel, however, cannot be overstated. His findings have been applied in plant and animal breeding, as well as in medicine and other fields. Modern genetics is the basis of current experiments in cell reproduction and cloning, and is a truly prestigious and celebrated science.

Most of all, Mendel maintained throughout his life a strong belief and hope in God, to whom he had pledged his life. His scientific work, particularly his experiments with pea plants, was not seen as contradictory to his religious beliefs, but as a means to helping others to understand God's creation. His commitment to his faith was evident in his sermons and other writings, which show his passion about sharing his beliefs about God with others on any given occasion. This month, we celebrate Christians who are scientists - those who study the brilliance of God's Creation, for they hold in their hearts two great commitments: one to Christ, and the other to a stewardship of the world God has made.

-Karen O'Dell Bullock

Posted in PeaceWeavers